On January 23, 2010, myself and ten other University of Miami students stepped foot onto Isla Isabela in the Galapagos for the first time, greeted by our fearless leader Johann. At the time, IOI stood for Isabela Oceanographic Institute and up until that point had been the Galapagos base for academic research and summer course sessions through the university. But our arrival marked the first time a group of American students would spend a full semester on the island of Isabela. Yes, you read that correctly: myself and my fellow classmates were the guinea pigs for this type of study abroad program. Our professors (and Johann I’m afraid) had no idea what we had in store for them. While we thought we were the ones shaking up the island, all 11 of us left the island three months later knowing that the experience we had lived was a privilege not many others get.

“On January 23, 2010, myself and ten other University of Miami students stepped foot onto Isla Isabela in the Galapagos for the first time”

We were asked to keep journals by our anthropology professor and prior to this writing, I read through mine and was struck first and foremost by just how young we all were—but I guess that’s to be expected. But then what I noticed again and again was tiny glimpses of a younger, more frivolous Katie giving way to strong, more mature, self-determining Katie. If I was searching for the place where my mind and my actions began to diverge from the path ahead of me, I think I would find it while walking home barefoot through the sandy streets after a long night of dancing salsa during Carnival. Being separated from everything we knew and suddenly presented with a different life entirely, one highlighted by convincing our teachers to re-arrange our lecture schedules so that the daily surf practice wouldn’t be disrupted; by realizing how much money you’re going to save on makeup and bras because you just don’t need them if you never leave the ocean; by learning Spanish overnight so that you can finally talk to your crush alone.

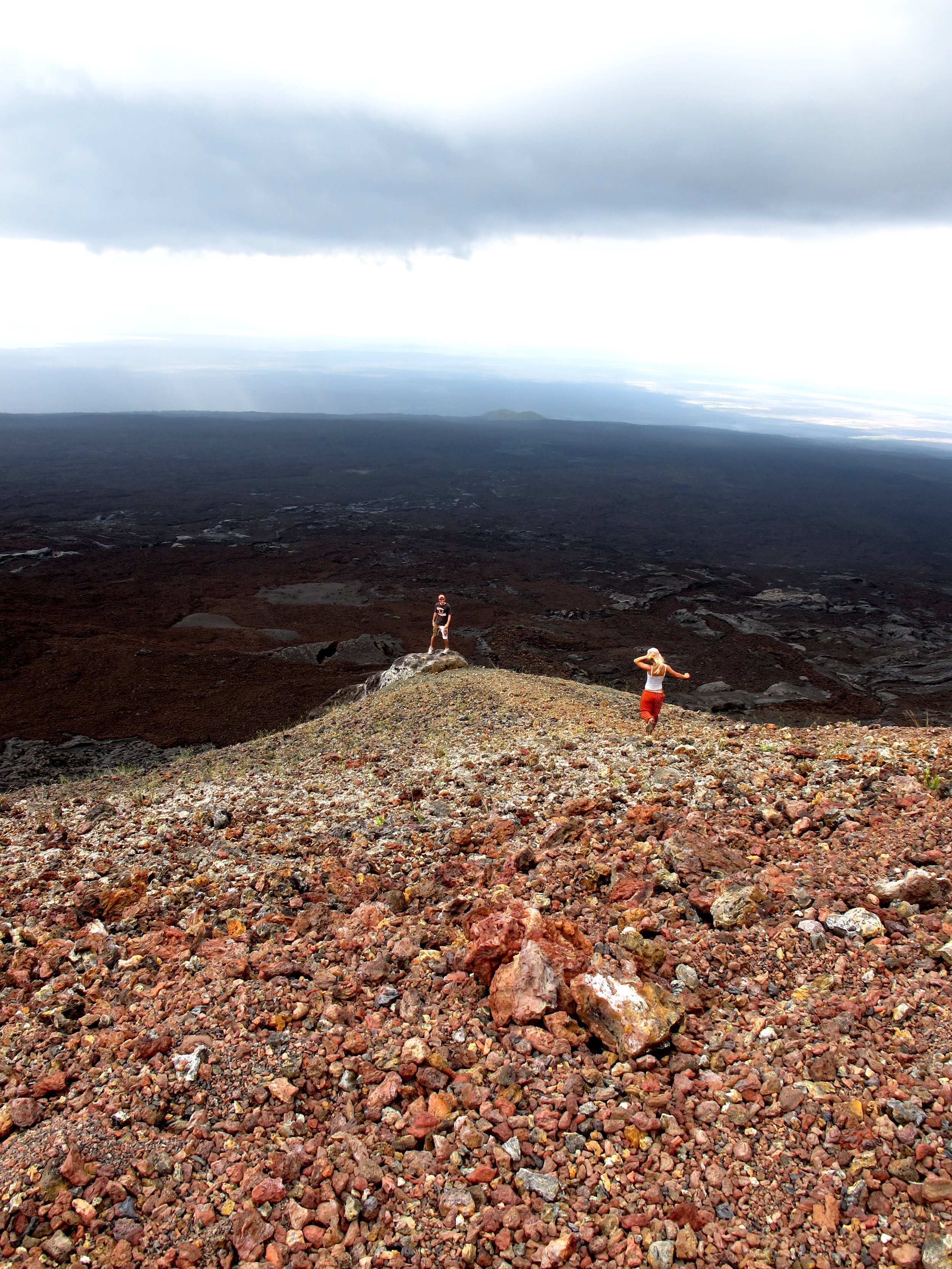

I would be remiss if I did not speak on the fact that we were provided the opportunity to experience some truly incredible moments. I will never forget swimming as fast as I could possibly could for as long as my lungs would let me just to get one more glimpse of that one manta ray or riding to the top of a volcano on horseback and camping overnight or deep-sea fishing and watching Sarah attempt to fight a clever and mischievous sea lion to keep her catch. I would also be misrepresenting my fellow travelers if I said we didn’t care about our actual coursework and while I am proud of the things we learned (I to this day remember more about damselfish that your average marine science major) in class, I am even prouder of the things we learned from the island and its people directly. Ultimately, we lived life differently for three months…and we loved it. We learned empathy for a place and for a society smaller, less connected, and further removed than most places we had ever been before. We made friends with the surfers and with the woman who got us ice cream cake for lunch. We grew close to our homestays families and called them our moms and dads, our sisters and brothers. Some of us fell in love. At the end of the semester, we held a boys versus girls island-wide scavenger hunt (the girls won). And on the morning we left, most of us cried.

When I started writing this entry, the pandemic was not on anyone’s radar. I wanted to write it in honor of the ten-year anniversary of an experience not one of us—Kat, Ryan, Petter, Aaron, Alex, Nikita, Chris, Judy, Sarah, Evan, nor myself—has forgotten. But nearly two years has gone by since COVID became a household name and I spent most of that time stressing about how to write an easy, breezy review of our semester spent living on Isabela. How do I wax poetic about my youth spent on an island while the human toll of a globally spreading virus grows every day? How do I balance the importance of highlighting my time in the Galapagos without shoveling saccharin nostalgia down everyone’s throats in the middle of a crisis? At the very least, surely by the now the curriculum has changed and adapted, how would my memories from a decade ago accurately portray the present and future of IOI?

It is now January of 2022 and what I have come to accept is that I have no idea what the world is going to be like going forward and neither does anyone else. I can’t make people feel better about studying abroad in a pandemic. We may not be able to cross borders or travel freely the way we once did but we can all stay curious, compassionate, healthy, and kind. I studied abroad with the expectation that I would, well, study abroad. But instead I was offered knowledge and wisdom in the form of someone else’s culture and the beauty and the weight of that is what I hold closest to me when I think back about our time on Isabela.